NFT Disputes Expose Legal and Cultural Shifts

Does the Digital Art World have a Consensus Problem?

After months of unbridled enthusiasm in the NFT community, inevitable legal and technical realities around the digital art marketplace have begun to set in. The NFT art world, existing somewhere between a bohemian utopia and a crypto-wild west, has seen some high-profile controversies in recent weeks that may be a sign of things to come.

While there have yet to be any significant court cases relating to NFTs, it’s become apparent that even the metaverse is vulnerable to the legal, social, and financial complications that affect the traditional art market. And in a world where Cryptopunks rule, it is unlikely that NFT country will see a sheriff in town anytime soon.

NO GUARANTEES ON THREE-OF-THREES

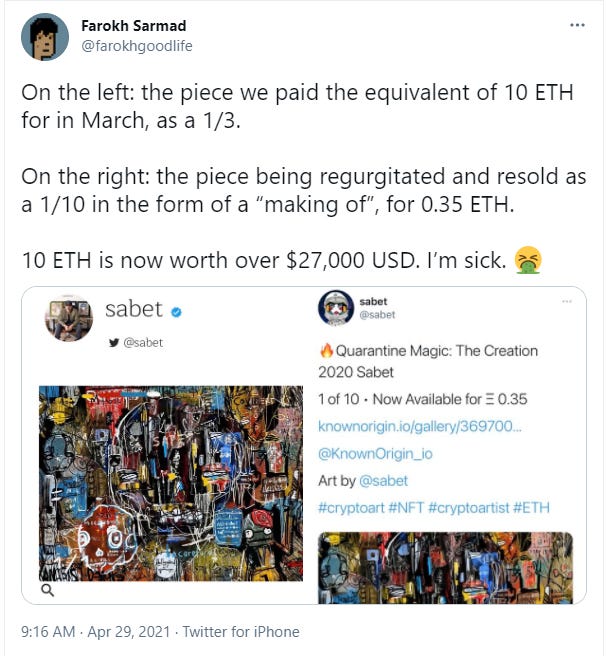

On March 2nd, the NFT artist Sabet minted an animated digital artwork titled Quarantine Magic in Motion offered in three editions (3/3). The first edition sold almost immediately for 10 ETH (approximately $15,000 at the time). The other versions were both purchased in the following days for comparable amounts. As with other standard NFT transactions, no intellectual property was transferred to the buyers and no guarantees were made about the scarcity of the three ‘prints’. The buyers of these NFTs presumably were aware of this.

Nevertheless, drama ensued several months later when Sabet sold a strikingly similar NFT entitled Quarantine Magic: The Creation 2020. The second artwork was also an animated piece which showed the digital ‘painting’ being created over time. Unsurprisingly, the release of the secondary work angered some in the collector community - notably NFT promoter and activist, Farokh Sarmad. Farokh is a known Clubhouse personality in the space and a collector. He also markets NFTs professionally and reportedly charges NFT artists to promote their auctions on Clubhouse and social media.

Farokh publicly condemned Sabet for selling the Quarantine Magic ‘re-makes’ and proposed as a remedy that Sabet return the money to the original purchasers of the Quarantine Magic in Motion piece and burn the tokens. However, it is unlikely that Farokh or the other purchasers have any legal recourse against Sabet for selling the subsequent works given that Sabet retained all copyright to the original piece — which by law includes the right to create and sell derivative works. Farokh and the original purchasers may have legal recourse in the form of common law remedies like fraud or misrepresentation or violation of state consumer protection laws; but those types of claims can be challenging to prove in circumstances like these.

As with the analogue art world, artists often sell limited edition prints of their work and, by law, reserve the right to distribute additional copies at any future time. For example, a photographer who auctions 10 limited edition prints of a single photograph is entitled to sell future copies of the work on postcards, t-shirts or even ‘identical’ copies in exactly the same size and format as the original limited edition pieces. But as a matter of traditional art culture, this is considered declassee and rarely done with high-profile works.

Creating nearly identical reproductions would damage the reputation of the artist which, irrespective of legality, is a sufficient deterrent. Moreover, some galleries or auction houses would likely refuse to display or sell these copies for fear of promoting poor artistic practices.

Part of the problem with NFTs is that there is not yet any shared culture around reproductions or derivative works of short videos, animations, or audio-visual works that derive their primary profit potential from NFT sales. For now, the principle mechanism for enforcing norms and punishing bad actors is via internal policing in the community, for example through shaming, and occurs almost exclusively on social media platforms. In this sense, the NFT community currently resembles the stand-up comedy world, where joke-stealing is primarily enforced through the tight community of performers and venues.

Notably, there are legal and technical solutions to these problems. For example, artists could offer, or purchasers could demand, a limited transfer of copyright or license to NFTs. Or an artist could include a contractual guarantee that similar works would not be sold as NFTs in the future. Indeed, for many NFTs including the popular Bored Apes Yacht Club collection, transfer of copyright is a central part of the marketing and community. However, transfer of copyright is relatively unchartered territory in both traditional and digital arts. And many artists are understandably reluctant to sell of their intellectual property rights, especially without careful attention to the legal details.

HOUSE OF BLUES

Earlier this year, contemporary artist Krista Kim sold the first ever digital home on an NFT marketplace for more than $500,000. Kim’s Mars House included a 3D digital file, rendered using video game software Unreal Engine, that the owner could register and experience in the metaverse or other AR and VR environments.

To create the visualizations for the Mars House, Kim hired Argentine 3D-modeler Mateo Sanz Pedemonte. Unfortunately, the Mars House has become the subject of a legal dispute with Pedemonte now claiming that he created the project and owns the full intellectual property to the meta-real estate. Pedemonte has stated that he is a co-author of the Mars House and has threatened to pursue the virtual property dispute in real world court.

Kim denies this account and has stated that the Mars House is her art creation and copyright and that Pedemonte does not need to be credited. Kim contracted Pedemonte to work on the project through freelance marketplace Freelancer.com and claims she did not agree to give him any intellectual property rights in the project.

Legally speaking, the matter simply comes down to whether Pedemonte created the visualization as a ‘work for hire”, in which case Kim would own the entire copyright. Alternatively, if it was a joint work, then Kim and Pedemonte would be joint owners and share the intellectual property rights.

Like many NFT collaborations, the matter could have been resolved in advance with an agreement that defined the artists’ respective rights. However, in the current world of NFTs, these ‘collabs’ often involve international partnerships, multiple parties contributing idea, and untraditional working relationships (that often include intermediaries and services like Fiverr and Upwork). In this environment, collaborators may barely communicate, let alone negotiate legal details around their work.

BRAVE NEW WORLD

Ironically, the blockchain community, which is fundamentally structured around community and consensus, may have a difficult time translating this harmonic art culture on-chain. The development of standard form ‘smart contracts’ and NFT platform tools and integrations will surely spur more experimentation with the ways NFTs are marketed, packaged, and sold. In the meantime, NFT purchasers will have to rely primarily on artist reputations and they are wise to abide by the ancient adage 'caveat emptor’.

One thing that’s certain is that these controversies will not be a one-of-one, two-of-two or three-of-three and we will surely see more editions of these stories drop in the coming months.

I am so grateful you wrote this article. Thank you very much indeed, Jesse!

It is really important to bring awareness in the middle of the ongoing enthusiasm. I believe NFTs can bring a world of opportunities to artists, but only if copyrights are respected... learning about self-management and licensing as well as looking for the proper legal advice is becoming a necessity to preserve Intellectual Property rights and make business with benefits for all.

Btw, congratulations for this newsletter!

Nice article.